2017|宮崎でむしをつかまえました。

Brown Hands Stained Blue: Stitching An Indigo Seam Between Two Identities.

October 2025 - September 2026

Rene Camarillo will produce a collection of hand made garments intended to highlight the migration of Chicano culture being adopted into various sections of Japan. Being born and raised in East Los Angeles, Camarillo learned about Chicano aesthetic influencing sections of Japan. This cross cultural exchange inspired and motivated him to develop garments which feature both traditional Japanese techniques with classic Chicano elements. The work he will develop for the Fulbright project will be grounded in new experience as he will be an apprentice studying under dye master Kenta Watanabe in Tokushima, Japan. Dedicating time working on Watanabe’s Indigo farm, Rene will study indigo cultivation and Sukumo production from the seed to dye. Furthermore, through Watanabe Farm, he will be granted opportunities to visit collaborative textile, weaving and sewing factories to assist in his studies and extend his apparel project possibilities. It is then, through a second affiliation with Kyoto Seika University that Rene will work with Mitsuhiro Kokita who will mentor him and provide expert advice with the production of an apparel collection. Rene will develop a collection of slowly made garments.

“I want the blue to stain past my wrists.”

2025年 10月

Color Research and Development。

I arrived in Japan on October 1st 2025. I currently live in Tsurumi, Osaka. In Japan everyone moves with a reason. I honestly do not fully understand how I got to fulfill this life changing chapter, but since I have been here in Japan I am constantly reminded that I am in the right place at the right time. The patterns of my breath have become more rhythmic since my feet have kissed Tsurumi.

I was caught in a light drizzle of rain in Kyoto, right after visiting the oldest incense shop in Japan (くんぎょくど - Kungyokudo established in 1594 for those of you interested) and was aimlessly wondering the streets when I found eating at an Izakaya reinforce my placement. The name of the Izakaya was いちしゅん (Ichishun) and the owner whose name is まんぞ (Manzo) kept glancing over at me and attempting to make small conversation. After savoring the delicious meal he had graciously prepared, he asks what I was doing in Kyoto to which I inform him I am developing research at Kyoto Seika University and how I study Apparel and Textiles. His eyes widened and became somewhat glossy. I can tell a special kind of spear picked his skin, and caused a smile to form at his aged face. He explained to me that his mother was also a weaver, and he had just recalled on a memory of him as a child hearing the sound of a wooden floor loom clack very loud with ever beat his mother performed while producing cloth as her employment. We discussed the simplistic beauty and dedication of patience as a weaver. Later, he thanked me for our conversation as I paid the bill and I continued my journey with a warm belly. Him, the elderly lady who lives below me and others continued to chant “がんばて ください”, which means please do your best. I get reminded that everything was making sense since I was lost in graduate school only five months prior.

Textiles, similar stories, and the history of cloth was constantly around me since the arrival in Japan. The whispering of the past hummed through Kyoto Seika University, and specifically I could feel that I was here for a reason and that my timeline overlapped precisely in Japan. I am grateful to be here extending my own textile and apparel contributions.

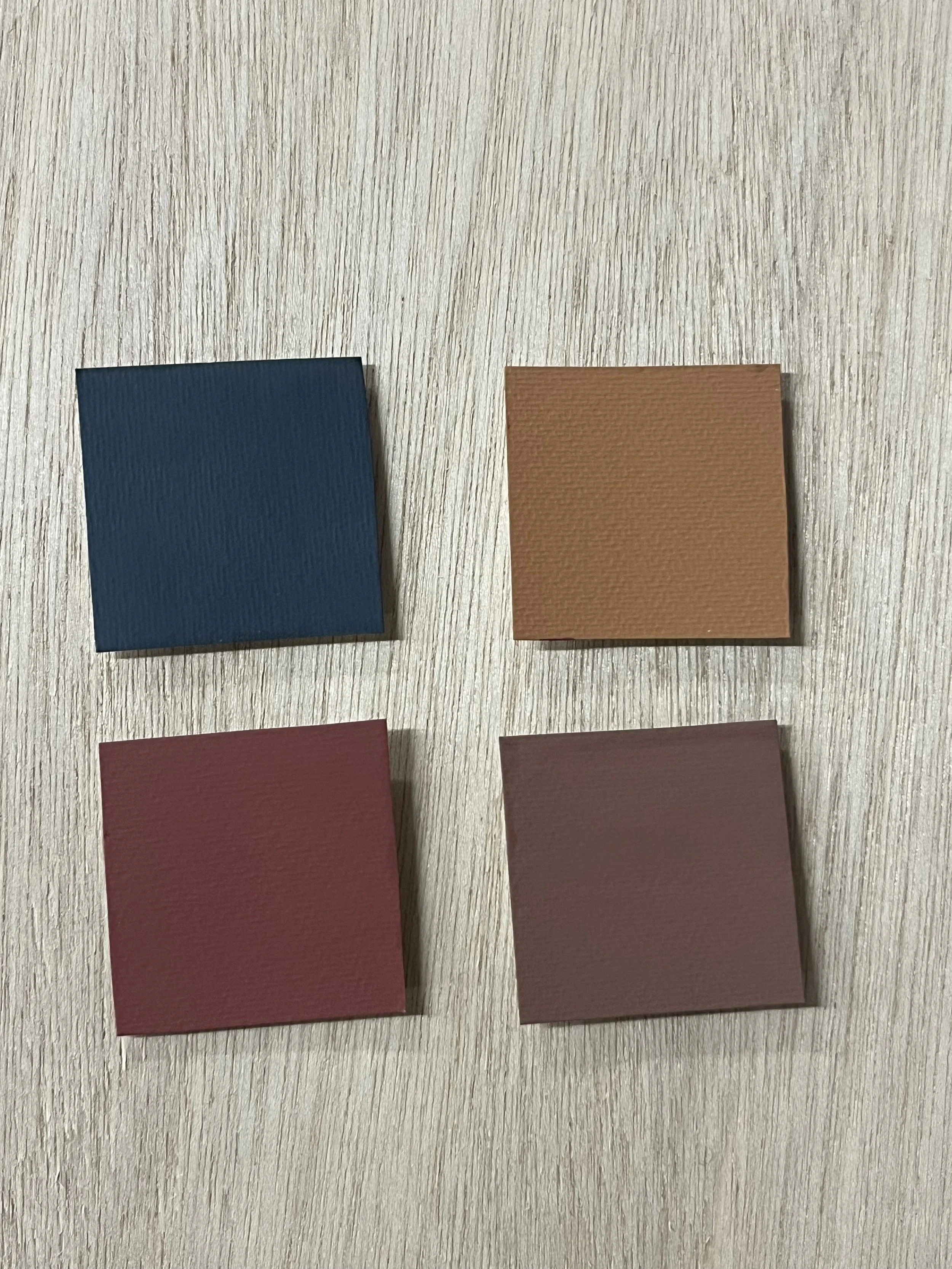

My research began with the development of color. Researching significant traditional Japanese colors I had aligned myself with. Colors intended for staining and dyeing the textiles I intended to develop both by hand or designed and industrially manufactured. One color in particular was that of かきしぶ (Kakishibu), a tannin which is made from Persimmon fruit. A material I was familiar with as I used it often in graduate school because it reassembles that of oxidized blood to me. For me its special. Kakishibu dates back to the 13th century and also finds usage on staining wood and acts as a natural lacquer.

I also drew inspiration of color from どろぞめ (Dorozome), which is a technique in where the natural element of mud in rice fields is utilized to dye textiles with a range of beautiful browns. The color results that takes place is a remarkable miracle as a chemical reaction between the tannin pigments of ひたち 木 (Hitachi trees) which grows mostly in specific locations mixes with the rich iron found in the mud. Dorozome has more than 1300 years of history in Japan. I was walking back to my train one evening after a whole day in the studio when I remembered a comment I received in my Textile seminar class. When my cohort and faculty critiqued my color developments, one student stated that my colors were really “muddy”. I loved this comment and I think its true.

Finally fixated on true alchemy. The “Japan blue” which comes from すくも (Sukumo), fermented leaves of the profound indigo plant. A decadent blue which through oxidation (and perhaps some mythical presence) allows dyed goods to shift from green to blue within seconds as oxygen passes through the cloth. At the heart of Tokushima Prefecture, on an indigo farm is where my intensive studies will be carried out through my hands. There is so much to learn from indigo cultivation. I am beyond humbled to have a hand and study each process.

These three spirits of color inspired my color palette for this developing collection and using gouache I hand mixed over fifty color chips, making final selections which I intend to reflect in the textiles I produce and apparel I make.

Again, In Japan everyone moves with a reason. Each step is directed towards something phenomenal it seems. I learned about a word in Japan. This word is, いきがい (Ikigai). Its a philosophical meaning which defines as finding your true purpose in life. A reason for living. A personal contribution we all navigate towards. I like to believe my life is devoted to making objects; specifically hand made apparel and textiles. My fingers make love to materials not keyboards. My hands grip various materials instead of shaking the hands of future technology. The noises of the looms. The songs of the insects on the farm. The whispering of breeze that dance around the tall trees. The sounds of the city and the hums of the transit system. They all speak to me at an unfamiliar amplification.

There is so much volume on the silent trains after a long day in the studio. But the trains continue to proceed and so will I.

Apparel is not mine. All apparel used as reference is from, Soerte.

すくも Palette。

どろぞめ Palette。

かきしぶ Palette。

2025年 11月

Introduction to indigo。

Working with one of the assistants who I later learned had worked on the farm with Kenta for many years) I was able to dye cloth in indigo. My nails and hands were left blue for weeks.

After (and before) that first day, I visited Tokushima other times. It is such a special place and is known for its purple yams, すだち (sudachi) limes, あわーおどり(Awa-Odori) traditional dance, and perfect indigo coloration because of the City’s location near waters and rich soil. I visited the local Awa - Odori museum and took a cable car to local temples.

“I want the blue to stain past my wrists.”

(Sections in this passage are taken from my journal )

2025 年 11月 13日

Today I woke up at 6:00 am (I remember going to bed a little past three am the night before). In the crisp morning I set out back to Tokushima. This time to Watanabe Co., an indigo farm to meet the owner, Kenta Watanabe for the first time. I took two trains, one being the Osaka loop line for the first time and I managed to catch the bus to Tokushima only minutes before departure. After a scenic ride on bridges over whirlpools in Naruto, I arrived in Tokushima just before 11:20 am and finally I took a taxi to the indigo farm.

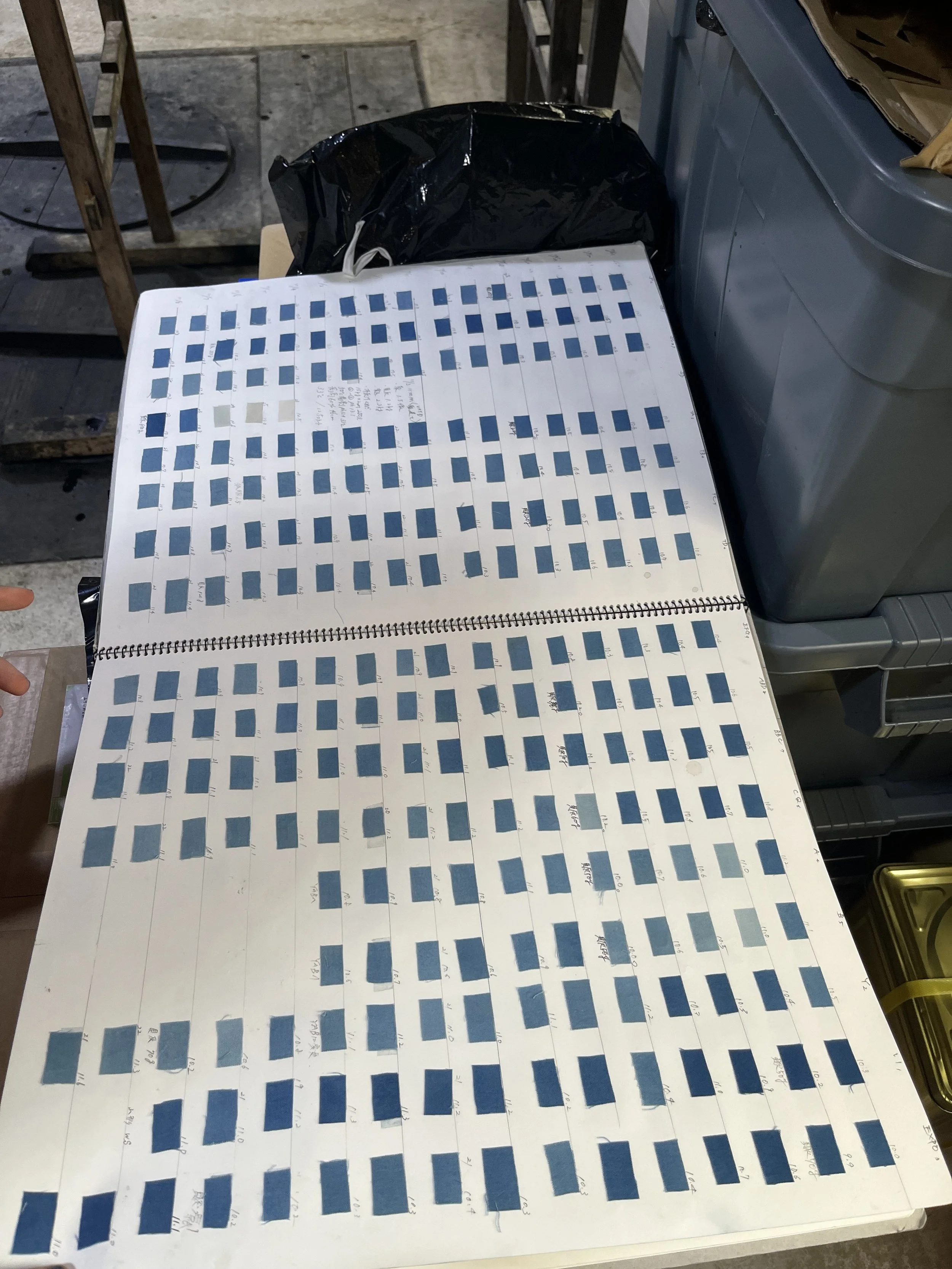

When I stepped foot on the farm it was 12:00 pm exactly and felt something thick in the air. When I met Kenta Watanabe for the first time, he spoke to me as if he knew me since childhood. His presence was very warm and intentional. I remember thinking his consistent smile highlighted his youthful personality. I fell in love instantly with the energy of Watanabe Farm. Kenta had four assistants, each just as welcoming and polite. His workspace was the perfect size and the fragrance of the Sukumo was really strong. At a table table covered in work materials and beside his indigo vats, Kenta spoke of infinite possibilities and how he was obsessed with the the blue shades his indigo produced. I glanced through a working notebook of his which showcased an array of dipped swatches. Each with a rich blue. To the average eyes, the blues trapped in these textiles seem so similar and obvious even; but to Kenta Watanabe they all are so vastly different (even the samples that appeared to be identical to me). We spoke more after lunch after a stop at a local Udon restaurant. I remember my body feeling lighter when we returned to the farm and I knew I was in the right place.

Back in 2023 while preparing and working towards early steps of my Fulbright application, I sent an email (among other aimless emails to countless companies in Japan) to Kenta Watanabe in hopes to study indigo cultivation and produce a pair of hand dyed jeans. Though I was in Providence Rhode Island at the time, our communication seemed inspired and authentic. In a strange way I could even feel his energy while still a graduate student at RISD through my laptop with each email conversation. Now, there I was. On his indigo farm. Standing right in front of him. Later after our introductions had passed, he tells me, “your work is confident and powerful” and ends his statement with, “but you yourself are the opposite, quiet and reserved”. He met me less than an hour ago, and like some type of fragile glass, he can see through me quite well. With that being said, my faith in this project becomes stained deeper in an unfamiliar blue.

2025年 12月

Okayama

こじま | くらしき

The freezing air somehow cut through each layer I adorned myself with that day. It was very cold and I was welcomed with very strong winds that pushed me through the streets just outside the train station. Okayama is rich in history. The prefecture’s historic past is woven seamlessly with the modern market. Okayama’s depth was projected by the dominating color(s). As potent as the energy of the city was the indigo blue which stained my memories as I first stepped foot in Kojima, the birthplace of Japanese Denim. Finally.

I spent most of my day getting lost on “Jeans Street” in Kojima. A street which displayed denim jeans as far as the eye could see. Jeans even hung on wires and buildings all around. I was fascinated by the handful of apparel businesses that entrusted their mass production methods towards producing slower derived products. Products which force entanglement with Japan's historic methodologies. I think for the first time in my life, my hands touched garments that were truly constructed after being dyed by hand meticulously with Japan's traditional indigo processes. Historic practices that continue to reach a newer generation through product development. There was of course, the brand, Momotaro which casted a shadow over other smaller denim companies on Jeans Street; but there was also lots of life and love sewn into products from other lesser known brands. I stepped foot into a small shop where all of the denim products were designed (and most even detailed by hand) by four middle aged women who decided to make denim their lives. I treated myself to a precious hand dyed indigo sweater. A piece produced by a small company known as Conoito Tsumugu. I wonder if I can ever do the same. Bring indigo practices back to East Los Angeles and build something of my own so I can secure my devotion and daily worship to craft.

はんぷ (Hanpu). This is the recurring word I discovered when I arrived in Kurashiki.

はんぷ also known as Kurashiki Canvas, is an historic cotton textile characterized by being a thick (and usually white) cotton twill weave. Cotton cultivation began in the early 16th and 17th centuries in Kurashiki and surrounding Bizen regions. The salty soil close to the sea allowed not for rice farming, but cotton farming instead. Soon after, undyed sailcloth made from handspun cotton developed from the meiji era (1868 - 1912) onward. Kursashiki produces 70 percent of Japan's cotton canvas. It is Japan's city of cotton and has history intertwined in trade with the West.

Throughout my life, I often wonder about the everyday social engagement of textiles and apparel. I’ve come to the conclusion that it is not the market nor companies, but consumers that ultimately determine the value of textile goods (or any goods in a capitalistic market schematic). Materials, craft and technology come at the forefront of mass production. The access to newer technologies, materialities, information and techniques ultimately is what allowed “trends” to allow consumers to determine values.

For example, Kurashiki’s peak canvas production was 21 million, but has now declined to 2.9 million. A decline left to nearly one tenth. With the changing times, the production has shifted from prioritizing sailboat cloth to tote bags and pouches as technology progresses the world to move forward. In these modern times, Kurashiki now produces most cotton for denim jeans.

It has nearly been three whole months since I began my research in Japan. Okayama and its impact has bruised me the hardest.

I have also been thinking about precious materials. Materiality is always so important to me. In a way, I feel like materials are what holds the spiritually in objects. In Kurashiki, I stumbled into many markets with historical elements. Ceramics, textiles, and an array of materials that spoke to me. I stumbled into a very lonely shop that sold mostly basketry that didn’t seem appreciated by the tourists that passed by. The store went uninterrupted as I browsed quietly, eventually leavening with hand made rope known as しゅろなわ (Shuro nawa). Rope to me is an important material because of the signals it transmits through semiotics. It always seems to renter my projects because of labors relation to it. As I develop my collection of hand made garments, I want to consider the inclusion of raw materials blatantly such as rope trim and entertain the idea of transparency through silk organzas.

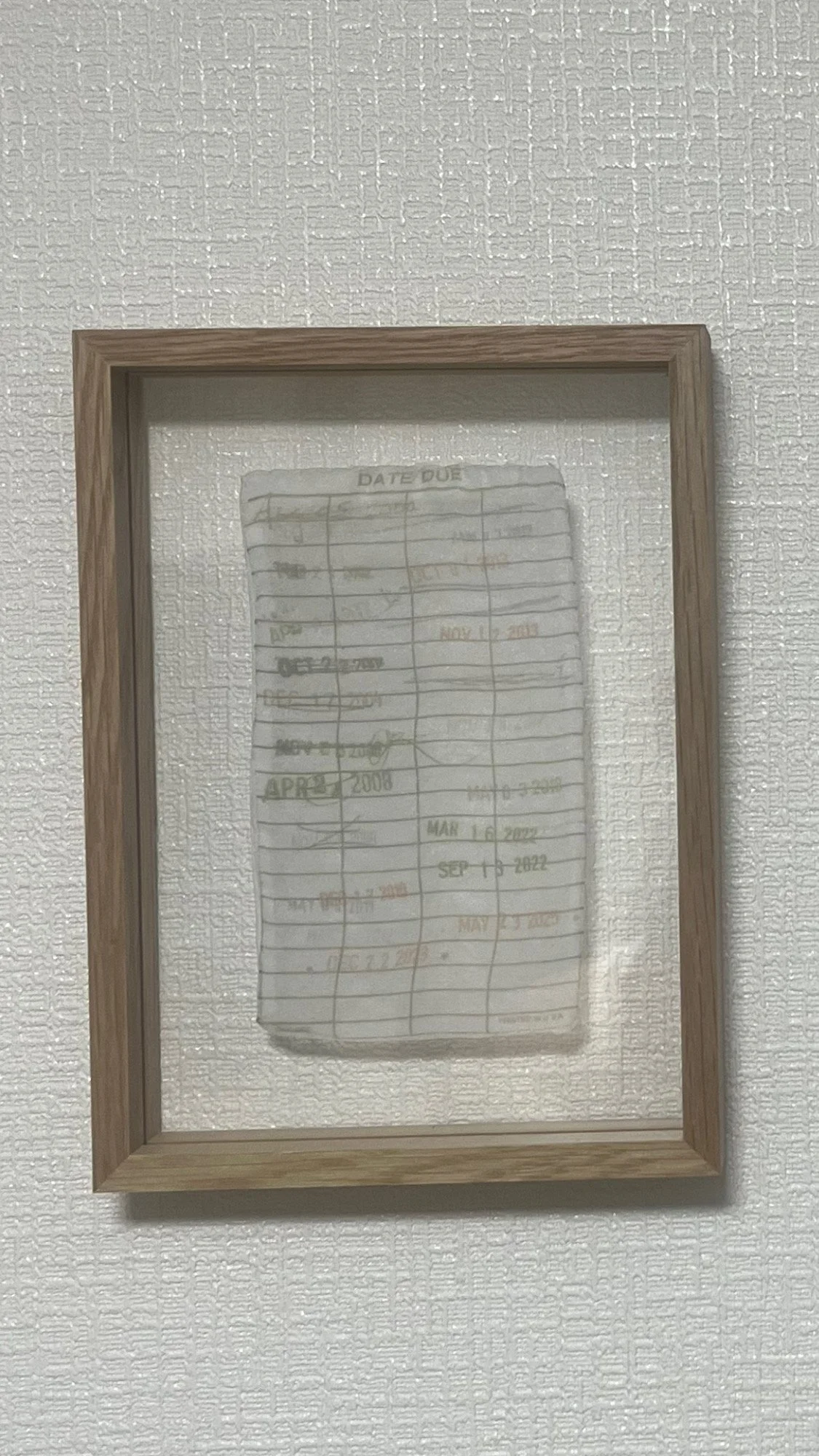

Back at RISD, I began working with silk organzas and their ability to posses aspects of memory in their shifting transparency. Here in Japan I completed what I would describe as a small “study”. After hand stitching, I framed a textile piece which is a dye sublimated library “Due Date” card of a book that inspired me in grad school (the book was “Weaving Memories by Hideo Yamakuchi for those curious). The sublimated organza holds the marks, scribbles, various color inks, and hand contributions of countless unknown people who left an imprint before me. Ghosts of the past. Transparency is something I may continue to guide me along with visceral natural materials.

Back to my apartment in Tsurumi I had an opportunity to be behind a small floor loom at Saori Toyosaki, a workshop environment. Suddenly my fingertips didn’t itch as much after I wove my cloth.

2026年 01月

“When I Think Of Craftsmanship I Feel Blue.”

After taking the Keihan train to Demachiyanagi station (the very last stop along with a bus ride), I found myself sitting on my knees in Inagaki Kiryou; a weaving supply shop in Kyoto established in 1897. My handwoven textiles were scattered around the floor and sitting across from me, also on his knees was Inagaki Ryutaro, a generational owner of the shop. My Japanese language was limited and his English language was limited, but we spent around an hour communicating through the translation app on our phones. As you can guess, there was a great amount of silence, yet a stark contrast felt in our rapid keyboard typing and crazy eye movements. We asked each other questions like “do you believe textile craft work is declining, and if so, would the digital age contribute to its extinction or assist in preserving?”. I remember also being asked something along the lines of “why am I trying to study hand weaving despite my generation proceeding with Jacquard weavings?” We spoke about the past, the future and the present generation of Japanese youth which seem to neglect traditional textile craft. We both felt this urgency to continue our work and the importance to keep the traditional slow processes of making very much alive as our world became more distant from hand making. We smiled, scowled, and at one point both lost in thought as we contemplated the survival of Japanese hand weaving.

At this time I held the urge to cry. This moment was far too concerning because we both understood the world we lived in and how it rejects and posits craftspeople and rewards fast manufacturing in the age of a market system. It was then when he requested that we walk to an all women’s weaving school and meet with Kikuo Hirano, a master Nishijin Tsuzuri-ori (a form of tapestry) craftsman who produces the most incredible pictorials with some of the thinnest yarns I have ever seen. With my shoes at the door, Hirano san hovered around his work studio with passion. Despite his age, I still witnessed a flame. He continued to ask me an array of questions and began to tear as he thanked me for having deep interest in preserving hand weaving. When I eventually slide the door closed behind me to leave, I can’t explain in but my feet felt much heavier. Like I didn’t want to walk away from this place and these craftspeople.

More into the month of January I found myself on Watanabe’s indigo farm again. I hand dyed four yards of some hanpu that I had purchased and began documenting dip dye tests. I assisted with the tending of their precious Sukumo (which is the fermented indigo leaves that is needed to produces the liquid dye) and had the privilege to make small studies. Collectively, once the Sukumo was tended to, we each prayed over it together.

Later, while working on Watanabe’s Indigo farm, Ryutaro emailed me a line that read, “I don't know if the future is bright or dark, but if you move forward passionately with methods that fit the present, I'm sure things will work out. “. I paused, took in the moment and carried on.

Before hand dyeing

After hand dyeing